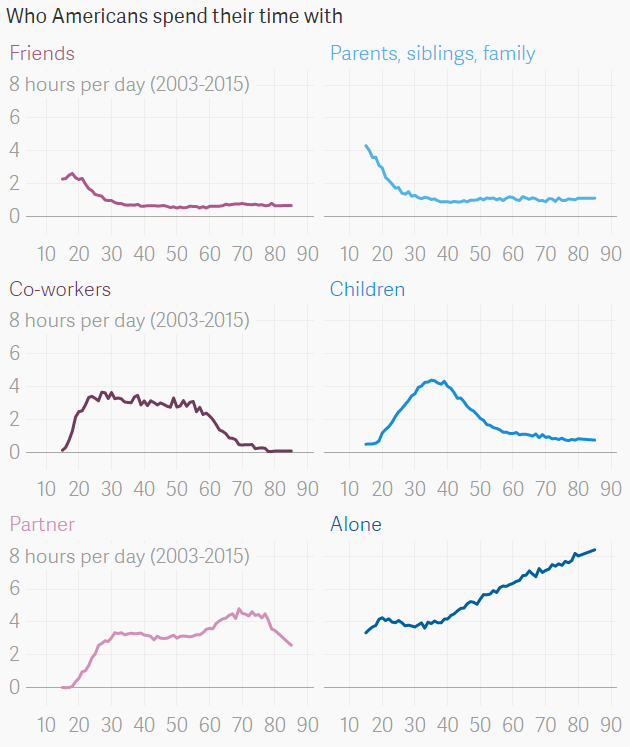

The above graphic from Quartz shows how much time we start spending alone after age 40. This isn't good for us, as I've touched on before.

(via Kottke.org)

Pay attention to the one on the lower right. Especially if you're male and over age 40.

(via Kottke.org)

*Big, big conflict of interest above. I get paid to do consulting for CDC and Kansas Department of Health and Environment to make the Diabetes Prevention Program a more accessible tool for physicians and their patients with pre-diabetes. But watch the video anyway.

Without a change in diet. Original study here. The usual caveats apply to this in terms of small sample size, yada, yada, yada, but the effect is in line with other research on the topic.

I'm skeptical. There is some confounder that is not being accounted for in this study, but I'll be darned if I can figure out what it is.

You can get a kit for this Lego drone from kitables, but it won't bring you a defibrillator.

We better hope those drones aren't noisy, though: a couple months ago I stayed in an AirBnB east of downtown San Diego for a few days. We were directly under the final approach for SAN, and except late at night, a plane would roar overhead every few minutes. Bad news for the people in that otherwise charming neighborhood: all that aircraft noise may increase their blood pressure.

The effect size is small (adjusted risk ratios for any birth defect were 1.05 for BMIs 25–29.9, 1.12 for BMIs 30–34.9, 1.23 for BMIs 35–39.9, and 1.37 for BMIs over 40.

It doesn't take this much blood, but still: don't check blood sugars if you don't need to.

I like this paper for a couple reasons: first, it confirms what I already thought, which makes it my (and everyone else's, whether they admit it or not) favorite kind of paper. Second, it's by my old boss at UNC-Chapel Hill, John Buse (seen in that picture rocking a Willie Nelson-esque beard). Finally, it's a very practical look at what glucose monitoring is. If you're on insulin and can change your dose meal-to-meal and day-to-day, it makes sense to monitor glucose levels for safety and efficacy reasons. If you're on fixed doses of non-insulin medications, the act of glucose checking becomes much less practical, and just as big a pain in the ass as it always is. My screed against SMBG in this case, though, is called into question by the study. The investigators measured "health-related quality of life" at 1 year, and it didn't differ between the groups. So the people poking themselves didn't feel much worse than those who got off the hook. But I'm sticking to my guns: when it comes to self-monitored blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetics NOT on insulin, the juice (that's your blood) literally isn't worth the squeeze.

I say "no shit."

Small, small study, and data not available in a peer-reviewed publication yet, but "After controlling for sleep duration, the laboratory study involving healthy volunteers found that compared to eating during the daytime, prolonged eating that began at noon and went as late as 11 p.m. was associated with weight gain, increases in insulin and cholesterol levels, and impaired fat metabolism." My previous warnings about data presented only at conferences applies here, but considering the apparent care put into the study, and its funder (NIH), this'll probably end up published.

It's been shown time and time again not to work, and it's expensive and weird. Stop it.

The idea that good diabetes care isn't strictly an obsessive quest for an A1c level of 7% or less is finally hitting the mainstream press. This article also touches on the very real dilemma that doctors and patients face: Do we use old, cheap drugs that are effective at lowering the hemoglobin A1c level, or do we use new, astonishingly expensive drugs that have better evidence of actually reducing death?

Most people will never understand my eating disorder. "I am six feet tall and between 180 and 190 pounds, depending on the month. I am by no means the picture of health or even particularly muscular-looking—not for someone who exercises this much, and definitely not compared to most of the men I see at my gym. Or maybe I am? That's the problem, or one of them: What I see when I look in the mirror doesn't correspond with reality. I see a fat piece of shit, and then I think to myself that it's time to punish my body for letting me down."

Do patients make mistakes during doctor visits because they're put in a position that forces them to rely on intuition and makes them vulnerable to biases?

I finished the Dirty Kanza 200 yesterday, and I plan to write about the experience in detail. But for now, I want to mention Warner Blackburn, a man who died during the 50-mile race. He was given CPR on the course by a friend of mine and taken to the hospital, where he died of an apparent heart attack.

I suppose the most cyclist-y thing to say is that "Warner died doing what he loved" or some such crap. But I don't know that. I don't know that Warner even liked cycling. He left almost no trace on the internet. Maybe he was doing the DK 50 on a bet, or maybe he was trying to support a family member. My wife makes fun of me because I automatically assume that people in cycling and other outdoorsy pursuits are nice, even though I'm not the warmest cuddliest type around. So I'll say this: whether Warner liked cycling, or whether he was trying to support someone else, or whether he was trying to support a cool event for the local community, he went out on a high note.

FWIW, for anyone thinking of starting exercising after a long period of physical inactivity, please take the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire first. It's a little too sensitive, meaning it may flag a few people who aren't that high risk, but if you have a "yes" anywhere on the form, it's worth talking to your doctor about before you go out and hit it too hard.

It's coming. The 2017 edition of the Dirty Kanza 200 is tomorrow, Saturday, June 3. I'm under-prepared. But I feel that way about every race I enter, as my notes from last year prove. Step into the time machine and travel back a year with me:

I knew going into the 2016 Dirty Kanza 200 (my first attempt at the full distance) that I’d under-prepared. I’d done a few long-ish rides in the spring: several rides over 60 miles, a couple over 100 miles, including the local Wicked Wind 100. I’d even spent a few days at altitude, climbing hard in Santa Fe and Albuquerque, but the last day of it was complicated by a sticky bout of gastroenteritis. My vomiting wasn't from the exertion, but it might as well have been, because climbing anything, at altitude or otherwise, has always been hard for me. I’d failed by a couple miles to summit Haleakala in February 2016. And I’d hardly started, let alone finished, Elrod’s Cirque in Winfield, thanks to an early mechanical on my coaster brake bike (I'd raced the Krazy Koasters division because of a chance of rain and a desire not to have my rear mech ripped off). So I’d given up hope on any real accomplishment at the DK other than finishing. There would be no real competition with my faster 40-something peers. I likely couldn’t sustain a pace to “beat the sun.” Finishing with a modest amount of suffering was my goal.

I felt like I needed to do some planning to make up for my lack of preparation. In the week leading up to the event, I tried to get on my bike for an easy-ish ride daily to keep my legs turned over without costing myself any rest. I strategized my food: I would eat protein at checkpoints and mostly carbs on the road. The protein would come in the form of Snickers bars and “PBJ Sushi” prepared by my daughter.

I would tear into a stockpile of stroopwafels on the road. Hydration would come in the form of water in a hydration pack and Skratch, a drink that has served me well in the past, in bottles. And even though the literature on it is sparse, I'm a fan of eating pickles at checkpoints, so I'd stocked up on those.

I intended to pack light on the road. Previous finishers had convinced me to treat the race like four 50-mile races strung back-to-back, and this seemed to make the likelihood of needing bulky provisions fairly low. So there would be no tangle bag, feed bag, or extra bottle mounts. Just my trusty, rusty steel Ritchey Swiss Cross, me, and the hydration pack. My wife, the Chief of Sunscreen Police, would tend to keeping me unburnt with ample sunscreen at each checkpoint.

I’m not a 100% glove-wearer, but for the sake of decreased hand fatigue I would wear them for the DK. I would, as a lifelong heavy sweater, wear a Halo sweat cap under my helmet to keep the sweat out of my eyes. The cap would earn me extra points from the Sunscreen Police for keeping my forehead and scalp covered.

Effort-wise, I planned to keep my heart rate around 130 beats per minute, a pace that my home experimentation showed my should 1) be sustainable for a very long time, and 2) get me to a ~14 mph average, depending on the roughness and grades of the roads.

I checked in and went to the riders' meeting, ate a huge Mexican dinner downtown, then retired to the hotel room to make sure all my gear was in order. After being awakened by a 3 am rumble of thunder and the sound of heavy rain, I slept fitfully the rest of the night and woke up early. I ate the complimentary breakfast at the hotel, then skedaddled downtown and lined up to start near the 15-hour sign. I was later getting to the starting line than I’d intended, and I’d walked my bike the three blocks from our parking spot to the start. So as the countdown began, I looked down and saw that my chain was off the front chainring. I unstraddled the bike to put the chain on and, thank God, noticed that my front cantilever brake’s (I’m old school like that) straddle cable hadn’t been re-attached after taking my bike off the rack.

Look closely at the chain and wonder to yourself how this bonehead expects to be able to move the bike down the road.

So as the leaders rolled out, I took a deep breath and re-attached the cable. I rolled out five seconds behind schedule and, relieved to find myself moving on a functioning bike, I forgot to his “start” on my Garmin until I was a half-mile or so down the road. It started without trouble, though, and the route popped right up.

South we rolled out of town, on a mixture of old-timey brick streets (“Kansas cobbles,” as they say) and pavement. The previous night’s thunderstorm had wetted the street. I was unsure how far outside town the storm had reached. As soon as the group hit the first right turn onto dirt roads south of town, order descended into chaos. Riders were charging through mud and standing water, and within two miles of town, they were already paying the price with broken derailleurs and clogged cogsets. Dozens of riders were in the ditches, working furiously on their bikes. Many of their days had ended 12 hours early.

I rode gingerly through the mud, watching my derailleur closely to try to keep from breaking it off (I've sacrificed more than one rear derailleur to the mud in my day). I had to stop pedaling at one point as a rock positioned itself perfectly between the chain and the pulleys and flipped the mechanism up behind the dropout. I was millimeters from suffering my own early abandon. But with a little caution and a lot of luck, I made it to the point outside town where the mud transitioned into gravel, and I was off.

Lucky socks, only partially caked in mud at this point.

The first checkpoint at Madison High School was challenging in that you had to follow a little spur road to get there, and since the riders were still fairly bunched at this point, it was hard to find my support crew. But after a quick phone call, I found her by the road.

I used a water bottle to try to rinse the mud out of my chain and cassette. Then, after a quick refill of water bottles and pockets, a couple pickles, a Coke, and a Snickers, I was on my way.

That's not cake batter on my face. It's sunscreen, applied by the Chief.

My apologies to the guy on the Open U.P. bike that passed me at about mile 85. As soon as we turned north into the headwind, I wheel-sucked him for several miles, then passed him as soon as the route turned east and out of the headwind. He didn’t seem flattered by my (sincere) compliment of his bike, and I don’t blame him.

Not the guy on the Open U.P. But a nice guy, as I remember.

We kept a nice tailwind from the north as we rolled toward Eureka. Some of the last few miles into town were even downhill, which felt great. By Eureka, the crowd had thinned, and I found my wife-slash-support crew easily this time. My chain was in dire need of lube by this point, so after the usual refills and a quick application of lube to the drivetrain I was on my way. Very uneventful stop.

Miles 100 through 120-ish were OK. I was riding either with the same tailwind we’d had all morning, or I was riding with a brisk but tolerable left-to-right crosswind. But the heat was starting to rise; blue mirages started to appear on the roads ahead. I actually saw a vulture circling. The heat and dry wind started to take their toll on my hydration somewhere around mile 120. That was about when I peed for the last time all day. Somewhere around mile 140 I took my last drink of Skratch (from a water bottle) or water (from my hydration pack). Then I entered a dark place. A dark, cotton-mouthed place. A wrestling match with a bicycle in a field of heated talcum powder. My tires rolled over a flattened, dry snake carcass. I was temporarily relieved by a four-wheeler driving dude hanging out water bottles at about mile 143. He limited me to one bottle, which was reasonable, and I poured it into my own bottle, thanked him profusely (I may have offered him a kidney. Things get fuzzy here), and took advantage of a descent eastward.

I descended a couple hundred vertical feet and drank half my bottle in one long pull. Then a river crossing came with advice from some volunteers who suggested that I ride through the foot or so of water instead of walking. I did as they said, and the cold water splashing up against my feet and legs felt incredible. It felt so good that I briefly considered stopping and sitting in it, but I didn’t like the idea of a wet-diaper chamois for the next two hours, so I pedaled on. Foolishly, maybe, I ate a melted Snickers bar and drank the rest of my charity water in the next mile or so.

It was about here that the cramps suddenly worsened. I had felt a familiar twinge in my right calf a couple of times, but it hadn’t progressed into a full-on cramp. I can’t explain the timing, since I’d just had some water, but once my dehydration intersected at just the right place with my muscle fatigue, and once I had spent some time going into the wind, a cramp seized my right inner thigh, then the left. I’ve done enough distance cycling to know this feeling. Stopping does not help. Stopping may make the cramping worse. There is something therapeutic about the forced circular motion of your feet. I embraced the therapy and kept turning the pedals.

Somewhere in through here I passed a guy in a green Salsa kit. Having forgotten the exact location of Checkpoint Three, I asked him where to look for it, mileage-wise. He good-naturedly told me mile 161 (we were at about mile 150 at this point), and I thanked him and moved on. My cramps spread into both calves. I became sufficiently desperate for water that when I saw one of the hundreds of inadvertently jettisoned water bottles on the route, I stopped, reversed course for 100 feet, and picked it up. Finding only ~10 ml of sticky, red, backwash-laced liquid inside, I sighed, dropped the bottle, and turned back north into the wind. By the way, a big shout-out to King cages here. The ability of everyday aluminum or composite cages to hold on to bottles in such bumpy conditions is overestimated, because in races such as this you see hundreds of bottles on the road or trail in the first ten miles, let alone the remaining 195. The most dramatic places are at the bottoms of hills, where full bottles have been bounced from cages. So Kudos to King cages.

Anyway: I was tired and thirsty and crampy. I wanted a drink of water. I rode by a restored foursquare house with outbuildings, a well-maintained flower garden, and some cattle pens. I turned into the driveway, laid down the Ritchey, and knocked on the door. No answer. I walked toward the outbuildings and called out. No response. About then, the guy with the Salsa kit followed me into the yard. I told him I didn’t think anyone was home. We agreed that the homeowners surely wouldn’t mind us using an outside hydrant. But we tried two, with no luck. The water was shut off to both. I cursed, rode toward a stock tank to make sure I wasn’t missing a hydrant, and failing to find one, rode on.

The dehydration and cramping, combined with forced physical exertion, had the effect of inducing an attitude of introspection and retrospection. Introspection regarding the choices I have made. Have I spent my days meaningfully? Have I wasted them? Have I taken my days for granted, or as a gift? This is not the thought of a dying or starving person. This wasn't a Jack London short story or the Revenant; my cell phone was in my empty hydration pack, after all, on airplane mode. Even though the cell coverage in rural Kansas is spotty, I could surely have thrown down a pin and had help within an hour or so. Retrospection for past bicycle-related follies, like the time I was stuck above 11,000 feet outside Angel Fire, New Mexico, out of water, with a wrecked bike, and forced to drink from a stock tank out of desperation, my reward of moisture having outweighed my risk of diarrhea from a mountain stream pathogen. I wasn't there yet.

A couple miles up the road I came across another farmhouse, and after following the same procedure as with house, number one, with largely the same results, I found a hydrant that yielded a trickle. I filled a bottle, dropped it, and spilled ~90 percent of the water, filled it again, dropped it again and spilled ~50%, and gave up. Mi amigo en Salsa was waiting for me to finish. I rolled back onto the road, back into the dust, back into the routine of pedaling and breathing, cramping and pedaling. The solitude of the Dirty Kanza is surprising. Nine hundred riders start, and for the first 50 miles you feel like you’re part of a swarm of ants. Then the group gets spread out, and by the time you hit the third checkpoint, there are times you can’t see another rider. It’s just you and the grass and the rocks and the sun and the wind.

A word on the people of Emporia, Madison, Eureka, and the surrounding areas of Greenwood, Chase, and Lyon counties: they have embraced this event. When I started spending a reasonable amount of time on the roads on bikes in the early 1990s, cycling, even mountain biking, carried a bit of a trashy, conceited euro patina that seemed to turn outsiders off. And this was right after LeMond won the Tour de France for the third time. I can’t imagine what the atmosphere in small towns was like before “LeMan” made cycling more familiar to a mainstream audience. Maybe it’s the gravel scene itself or maybe it’s a move toward everyone, rural, urban, athlete, or otherwise, being more accepting of cyclists in general, but I encountered nothing but smiles, waves, and courtesy in my fifteen-plus hours and 200-plus miles of the DK. On two separate occasions, a diesel truck--long the natural enemy of the cyclist--passed me with an outstretched arm ringing a cowbell.

With the encouragement of the locals I rolled on into Eureka, caked in salt, feeling completely fatigued. I used the lawn chair my wife had brought for the first time all day. I aired up the tires on my trusty Ritchey and sat both of us in the shade. I plugged in the external battery to my Garmin just in time to avoid it going completely dead, and I sat. Then I sat some more. I didn't keep time, but looking at the splits on my race, I suspect I was there for at least 30 minutes. I eventually resigned myself to needing to get back on the bike. I checked my hydration pack and my two bottles. I felt through the left pocket of my jersey to confirm it was full of goo and stroopwafels, and I rolled out. Slowly.

Cockiness gone. Replaced by salt oozing from my skin, iguana-style.

I tried to concentrate on things other than the discomfort: the constant crunch of gravel, interrupted only occasionally by the soft whoosh of knobby tires on rain-softened clay or the splash of a water crossing. The chatter of grass in the first two hours had given way to the soft sway of adolescent corn stalks in the 13th and 14th hours. I concentrated on keeping my breathing low and steady.

It was a while until I was able to get on top of my cramps, but I eventually did. At about mile 170 my Garmin, with the external battery plugged in, gave me the “turn off in 15 seconds” warning. I X-ed it out, but then It did the same thing twice more until, at mile 199-ish, I missed the warning and let it shut off. I panicked al little because, 1) I didn’t want to lose the data (few classes of athletes, I suspect, are as paranoid as cyclists in regards to losing proof of their effort), and 2) I didn’t know the route from memory. I didn’t want to try to navigate home by cue sheet in the dark. The red flashing taillight I’d been following had dropped me or become otherwise invisible. I was too proud to wait for a follower to catch me. Fortunately, when I hit the power button, the Garmin lit back to life just as it had gone to sleep. I unplugged the external battery and tucked the cord away. I double-checked my headlight and taillight and put my head down.

About the time I entered Emporia city limits, a couple guys caught me, then we caught a couple more, all of which led to a nice little rotating group for a mile or two. I was able to tuck in and go fast for a while, all while getting some rest, what with the draft and the intermittent pavement. Sweet Lord, the pavement. There’s not much, but the few miles of pavement mix in give you needed relief. The feel of pavement after 200 miles of gravel, mud, grass, and water is soooo good. Think of pushing a shopping cart across rough parking-lot tarmac, then hitting the smooth linoleum of the grocery store. It was like that. Only better because, see, in the Dirty Kanza 200, you’ve earned that smooth feeling.

But then, with some complacency setting in on my part, we missed a right turn by about 100 feet. I swore at myself, turned the bike around, and made the turn. I was getting impatient at this point, so when we finally made the turn and regrouped, I abandoned the (admittedly thrilling) nocturnal paceline and went to the front. After a minute or so I realized that the paceline was intact, but was no longer rotating. I was driving. In a fit of hypoglycemic, hypoxic grandiosity, I actually thought to myself, “I’m going to drive this train home.” Those who have spent any time with me on the road know the absurdity of this thought. But on I pedaled until I saw a stop sign and approaching car lights from the south.

“Car left!” I called out in the usual cyclist parlance, and I braked for the sign. My compatriots in the paceline, maybe feeling a bit hypoglycemic/hypoxic themselves, didn’t even pause.

“I think we’re good,” I heard one of them say, and they cheerfully blasted through the stop sign as the approaching car slowed. I waved, sensed that the car was going to wait for us, and got back on the pedals.

The final couple miles of pavement up the final climb through Emporia State then downward toward the chute with cowbells in my ears made me feel like Superman.

That guy looks so happy to be off his bike.

I took 20 minutes for photo ops and a beer. When I got back to the hotel, I showered and fell almost immediately into bed. Then I immediately got back up to walk off a cramp in my foot. Then I laid back down and felt the beginnings of a chill. My mind settled into sleep, but I didn’t feel the familiar, reassuring drift toward family or childhood memories. I felt the sudden, intermittent jerks of fever dreams, of heat and thirst and middle-school rejection. The jerks woke me, and I had to get out of bed from time to time to stretch a cramp or to go to the bathroom. The trips to the bathroom were welcome. I hadn’t urinated for 12 hours before, so even though urination burned a little and my bladder never felt empty, and even though I would discover the next morning that my urine was a burnt orange color, it felt reassuring to know my kidneys were back in business. After each urination I would fall back to sleep and feel the suffocating heat on my face. Adjustment of the hotel’s A/C did not help. I briefly feared that I'd picked up a bug, or contracted old-timey "dust pneumonia." (after this kind of effort, your mind may not work exactly right. But by the next morning, though, all was well.

Why ride a bike for 15 hours? Doesn’t the law of diminishing returns start to apply? Well, no. The 14th hour on a bike is only slightly like the first hour. And to experience the change from giddy excitement to cautious anticipation to pained determination, to experience the camaraderie first with enthusiastic pace-leaders, then hopeful bike-pushers, then finally determined, steel-faced stragglers, you need to have those middle hours from two to 14. You need to feel that first tug of a cramp in your right calf progress to an annoying knot, then you need to wax nostalgic for the cramp once it’s gone.

About 48 hours after the ride, my butt was back to normal. No more numbness. The soreness in my legs reminded me of the four hours of cramps I’d had; cramps bad enough to notice, but not bad enough to limit me, really. My hands, counterintuitively, were weak enough that it was hard to write longhand. My pinkies were numb. My neck, shoulders, and back were surprisingly unaffected, considering my lower back gave me some trouble during the ride.

Meeting these aches and pains was inevitable once I’d made the decision to do the Dirty Kanza 200. But they were a small price to pay for the rest of the experience: the view of waving, chattering grass, long vistas, natural water crossings and bridges. The comaraderie. The encouragement of the locals, with their ringing cowbells in the dark and the Emporia State students cheering us on as we rolled through campus.

People who don’t ride bikes, like people who’ve never been in love, think that the middle and the end must be the same, too. But if you last long enough, if you push through those initial bumps and slips, you find out that the middle and the end are what you were really looking for. And you know what? After the soreness was gone, I actually missed it. But I know where to find it again: tomorrow, June 3, 2017 in Emporia, Kansas.

Michael Bliss, author of The Discovery of Insulin, has died. RIP. I read his book while I was an endocrine fellow, overlapping, ironically, with a trip to Toronto for the Endocrine Society conference. His work was accessible, non-academic, and revealing.

“Family-based weight loss therapy sessions worked just as well whether children attended or not, as long as their parents did,” researchers found in a “two-arm trial” that included “150 overweight or obese children ages 8 to 12 and their parents.” Parents, your work with your children matters a lot.

Whole-body vibration may be as effective as exercise in mice. Color me skeptical. I first heard of vibration for metabolic disease in a presentation by an astronaut in college in the nineties. And, in spite of the plethora of machines available claiming to vibrate you to better health, the science just doesn't seem to have advanced that much. I'll skip my vibration sessions for the time being.

If you're overweight, combining aerobic exercise with strength training has the biggest effect on frailty. This is a small, but exceptionally well-conducted trial that is getting press because 1) it got into the New England Journal of Medicine, easily the most influential medical journal in the world, and 2) it addresses a functional outcome, not just weight. It seems to go under-recognized that obesity leads not only to inferior cosmesis and an increase in heart disease, sleep apnea, arthritis, and what not, but that it actually makes people frail. In my time running a medical/surgical weight loss clinic, we routinely asked incoming patients if they were able to get themselves off the floor in case of a fall. The patients were almost always surprised by the question, but many of them, after some thought, said that no, they would not be able to get themselves up after a fall. They were that frail.

Speaking of exercise, your watch or other wearable sucks at telling how many calories you've burned. This isn't a surprise, given the disparate results I've seen from my old, broken Nike Fuel Band, my Garmin GPS, and apps like MyFitnessPal. And even though I've never heard of the Journal of Personalized Medicine before ten minutes ago, the methodology of the paper is solid. But the results were best, strangely, with cycling. This gives ammo to the old argument that people who like data (speed, weight, power, HR, etc) are naturally drawn to cycling.

Who? This guy.

A patient once 3-D printed this owl for me. It was pretty badass. But nowhere near as badass as a functioning 3-D printed ovary that allows mice to get pregnant(!).

Kids who eat meals at regular times, go to bed on time, and don't drool in front of a screen hours a day have a lower risk of obesity later in life. Huh. "Three-year-old children who had regular bedtimes, mealtimes, and limits on their television/video time had better emotional self-regulation. Lack of a regular bedtime and poorer emotional self-regulation at age 3 were independent predictors of obesity at age 11."

Are the flame retardants in your house putting your cat (and you?) at risk of hyperthyroidism? As much as I'm fascinated by the topic, I'm even more in love with the idea of an "animal endocrine clinic."

(note: this is a continuation of a rant from a couple weeks ago)

I know it's absurd for me to be talking about "social media" as though it's some homogenous monolith. I'm sure aficionados could tell me the subtle differences between platforms the way a sommelier could tell me the difference between a Malbec and a Cabernet. But at the end of the day, those are just two varieties of red wines, and like them, Instagram and Twitter are more similar than they are different. And one of their similarities is they tend to bring out the worst in us.

Before my departure from social media, I saw people on Facebook joining or "liking" pages devoted to searing hatred of immigrants. These same people in some cases had testified at deportation hearings for undocumented family friends. What was it about the choice architecture of that "like" button that made the sort-of-evil decision the easy one?

This isn't that different from the other happiness-draining things our consumerist society throws at us with the promise that we'll be happier if we use them. Tobacco, junk food, and social media all want the same thing from you: they want to take away your control over your life, health, and happiness. But while we've made strides to combat tobacco and junk food, like smoke-free laws and taxes on bug juice, we seem stuck in a self-sustaining vortex that tells us that more connection, more technology, will solve our problems instead of creating new ones. If a drug hit the market and prompted some of the behaviors that we see with social media, would we applaud it?

And the children. The children. We're training our kids to avoid boredom at all costs. How many kids have you seen dialed into a phone at a restaurant? How many staring into a screen at a playground? How many being beseeched to turn down their phones while at a restaurant or basketball game?

These are not behaviors that any of us are proud of. Were you to point them out to the very people exhibiting them, they would be ashamed, right after they got done telling you off and posting on Facebook about what a jerk they just ran into at the restaurant. But pride aside, there is probably real harm being done here. I'm frankly suspicious of any claim that the fake news on social media swayed the last US Presidential election, but it certainly didn't lead to a more erudite, informed electorate, either. But a kid who sits at a restaurant with earbuds in, staring at a screen, is being trained that boredom is unacceptable. What will happen to this person the first time he's confronted with a situation that requires delayed gratification or an attention span?

So even though I'm a bit of an anti-incrementalist, I'm hoping to see just a series of small ticks in mobile/social media use. Comedian Chris Rock is having fans lock up their phones at his shows. Jack White has been doing it for a while now. I don't think these guys are doing it out of general fuddy-duddyness; they're trying to bring out the best in their audiences and to make sure everyone has a shared experience. Schools, historically afraid of parent backlash to less-than-100-percent-available kids, are even in on the act, establishing "phone free zones" with the same technology Chris Rock is using.

Bike Share ICT is official. Errr...was official on May 4. But since I've been out of town in sunny San Diego (stay classy), I haven't had a chance to post on it.

That speaker is Becky Tuttle of Health ICT (and who's soon *sniff* leaving for the YMCA), who was the driving force behind getting this done.

That Bike Share ICT is using no (as in zero) taxpayer funds? Check out the sponsors on the homepage.

That bike shares are associated with a reduction in traffic congestion, even when car lanes are converted to bike lanes?

That bike share users are far less likely to be injured than people riding their own bikes?

That bike lanes and bike share are associated with an increase in life expectancy, even for people who don't use them, presumably because of reduced air pollution?

The reason I'm excited about bike share is that my body was made for movement. When we see people in motorized wheelchairs, we feel bad for them. When that fancy motorized wheelchair says "BMW" on the hood, we envy them. That's dumb.

I need one of two things in a commute: Either make it fast, or make it slow. That is, I want it done and over with quickly, like when I ride my bike to my local grocery store (~1 mile away), or I want it to last long enough for me to get something done, like the guy Cal Newport writes about it Deep Work who bought a round-trip ticket to Tokyo so he'd have undistracted time to finish a book (thus giving it the biggest carbon footprint of any book, ever).

Driving a car usually accomplishes neither. Most people can maintain a 10 mph average on their bikes without killing themselves, at least after some practice. So 10 miles takes an hour, 5 miles takes thirty minutes, 1 mile takes six minutes, etc. You can start using this to budget your time. The library's 2.5 miles away (15 minutes). The grocery store is one mile away (6 minutes). It saves me less than three minutes on that ride to the grocery store. The amazing thing is that the times are so short. In my car clown days, I was accustomed to allowing 15 minutes wherever I went, short trip or long trip. Commuting by bike makes me more thoughtful. But even when I tell you it takes me 45 minutes to commute one-way by bike to work some days, does that sound like a lot of time to you? What if I told you that the average American spends three hours a day on social media? What if I told you the average American spends five hours and four minutes of each day watching TV? What if I told you that 79% of Americans don't meet the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, which encourage 2.5 hours a week of vigorous activity?

What if I told you that, if you would only ride your bike to work, none of that would matter?

Yeah, you'll sweat a little on your Bike Share bike. On hot days, you'll sweat a lot. Trust me: if the Olympics awarded medals for sweating, I'd be in the running for the gold, year-in and year-out.

I'm the Usain Bolt of perspiration.

If there's an eightfold difference in sweating between people, I'm so far on the "eight" end of that spectrum that I'm practically a "nine."

But that little hint of sweat you carry around: that's your reminder that you've done something with your day. While everyone else was phone-droning for three hours or watching five hours of TV, you were at least getting something done. You were getting your body to and from work, or the grocery store, or the post office, at the same time that you were making yourself healthier and making the planet *this much* healthier. And you saved money, too.

Your dog won't protect your kid from type 1 diabetes. This goes against the theory (which I tend to agree with) that "eating dirt protects us from autoimmune diseases."

Gluten-free diets don't appear to cut heart disease risk. Let me get this straight: celiac disease affects (thankfully) a very small fraction of people. For the rest of us, going gluten-free may increase our risk of diabetes and doesn't seem to have other beneficial effects. So why are so many people going gluten-free?

More and more companies are bringing out closed-loop insulin pumps.

Effect on empathy unknown.

Even though it's pretty easy for me to lose myself in a good book (the first one I remember this happening with was 4B Goes Wild, by Jamie Gilson), for much of my life I had the feeling that reading fiction was a waste of my time. I think this had to do with opportunity cost; I spent such a large chunk of my life as a pre-med, then a med student, then a post-grad trainee, so I just didn't feel like I had the time to read anything that I wouldn't eventually be tested on. I was so cynical, in fact, that I read The autobiography of Malcolm X just so I would have something to answer medical school interviewers' questions with. And sure enough, one of my interviewers asked me about the last book I read. I don't think the "mic drop" had been invented in the 1990s, but whatever the equivalent was, I performed it in that tiny room with my good-natured inquisitor. Even that level of cynicism was rewarded, though, as I came to appreciate Malcolm X and his movement in an empathic, layered way that would have been impossible without having read his book.

As my hard-core academic career transitioned into my current medical consulting gig, I found the time again to really dive into books. I even took an intro to writing class taught by the excellent Amy Parker. My new reading habit and my toe-dipping writing hobby aren't because of any delusion of grandeur. I don't expect to see myself on the best-seller list any time soon. They're my therapy. I guess that makes you, reader, my therapist.

Every time I enter my local public library, a sign tells me that reading fiction increases empathy. I don't know, because I haven't asked anyone with the Wichita Public Library, but I suspect they're basing the assertion on a series of studies by Emanuele Castano and David Kidd in which they randomly assigned readers one of several types of material: literary fiction (like Louise Erdrich), genre fiction (like sci-fi or romance novels), non-fiction, or nothing at all. Once the readers were finished with their assigned excerpts, they took a test that was meant to measure their ability to "comprehend that other people hold beliefs and desires and that these may differ from one's own beliefs and desires," or what they call the Theory of Mind.

What they found was surprising. Reading non-fiction didn't do much for readers' ability to know and understand the emotions and thoughts of others; it was no better than not reading at all. (this bodes poorly for the Theory of Mind of the readers of this blog) But reading literary fiction markedly increased this ability in readers, moreso than even the genre fiction. The authors theorize that literary fiction, by focusing less on the whiz-bang of the story and more on the thoughts of and relationships between characters, forces the reader to "fill in the gaps" to understand their intentions and motivations. Then, they say, this "psychological awareness" may carry over into the readers' own real lives.

I think I have some experience with this. When I was in medical school, Dr. Gerard Brungardt assigned The Death of Ivan Ilyitch to all students rotating through the geriatrics clerkship at the University of Kansas. Given the results of Castano and Kidd's studies, it isn't hard to see why. If students are dealing with dying patients every day, surrounded by their families with their conflicts and hidden desires, it surely helps students to be exposed to literary fiction told from the perspective of a dying man.

The implications of this finding are potentially broad. Should politicians be encouraged to read literary fiction told from the perspective of someone who disagrees with them? Should burnt-out endocrinologists be encouraged to read literary fiction about people mad that their doctor won't increase their thyroid hormone dose? Maybe I'll never feel chronic fatigue syndrome, and maybe medicine won't ever come up with a way to treat it, but I could read, learn from, and relate to characters I meet in an appropriate work of fiction and then apply those lessons to patients, right?

So even though my interests are broad (some might say attention-deprived), I try to sprinkle some fiction in with my technical reading, long-form journalism, and self-help. I like to have two books going at a time, ideally one fiction and one non-fiction. I can't prove it with a Science magazine study, but I hope the fiction increases my Theory of Mind and the non-fiction gives me insight into some part of my life I might've otherwise left unexamined. Right now the fiction-life improvement diad consists of Catch-22 by Joseph Heller, a book I amazingly made it out of high school and college without having read, and Just write: the art of personal correspondence by Molly O'Shaughnessy, a meditation on letter-writing disguised as a how-to manual.

And I'd love to see what Castano and Kidd's research would show about books on tape. I just finished The Black Lights by Thom Jones, read by Rachel Kushner:

Diabetes status unknown.

This author says the diabetics will be the first to meld with machines. I think everyone with a pacemaker may take issue with that statement. The first closed-loop insulin pump is a sign of what's to come though.

Alternate-day fasting is no more effective than good ol' fashioned dieting for weight loss. Aaaand, people on alternate-day fasting were a lot more likely to quit the diet. HDL went up a little more in the alternate-day fasting group, but other markers didn't differ between the groups. I think there is promise to "fasting" insofar as that means just not continually stuffing food into your mouth between meals. I'm less convinced of any benefit of intentional witholding of calories for days at a time.

Man, Kottke.org has been on fire lately with health-related videos and links. Above is a sweet demo of four ways to put roads on diets to reduce congestion and increase safety.

And then there's this little micro-documentary on a guy who tries to do a DIY-style fecal (and skin and nasal) microbiota transplant. This definitely falls outside the guidelines for the procedure.

And finally, the story of a science writer who turned a Seinfeld episode into a "case report" for an open-access journal and got it published. I've linked Kottke's page because he does such a good job of explaining it and has all the relevant links. The chief complaint and history (but minimal physical examination) are here:

No shade intended for Piscataquis County, ME. I can tell you that much.

What are Americans dying of? Spoiler alert: obesity. Second spoiler alert: complications of diabetes.

Artificial sweeteners may be associated with stroke and dementia risk. I've mostly given up artificial sweeteners, but not because of this paper. I'm making a bit of a Pascal's wager on artificial sweeteners: they're surely not good for us, even though they may not be as bad as sugar itself. So I take steps to avoid them, just like I take steps to avoid sugar itself. The fact that this paper didn't show any risk associated with sugar-sweetened beverages makes me a little suspicious of its results. Maybe the editorialists' note that people sometimes switch to diet soft drinks after they are flagged as "high risk" by their doctors is right. They're on their way to a stroke one way or the other, and they just happen to have switched to a diet drink beforehand.

Garden City, Kansas voted to raise the legal age for the purchase of tobacco or e-cigarettes to 21 years. The decision "grew from a request made by a group of Garden City High School students earlier this year." Garden City is the fifteenth (!) city in Kansas to make such a decision.

Exercise may help cognition (that's the thinking part) in the elderly. Seemingly if you work moderately hard for at least 45 minutes. What is moderate? According the ACSM guideline they used, it is hard enough to use "40%-60% heart rate reserve." That means halfway between your normal resting heart rate and your maximum heart rate, which is usually calculated by subtracting your age from 220. So if your normal heart rate is 70 and you're 50 years old, you have a maximum heart rate of ~170, so using 50% of your heart rate reserve would mean getting your heart rate to ~120. Confused? Well, "moderate" intensity is also about a 5 or 6 out of 10 in perceived exertion. There.

The FDA is warning (again) about bogus internet cancer treatments. A couple observations here: 1) I can't believe it's only 65 products. That must barely scratch the surface. 2) I don't know if the fact that so many of the products are co-marketed for cats and dogs is a good sign or a bad sign. 3) Even a casual observer must be astonished that we know so much about how to prevent cancer, and it's not complicated, and it's generally cheap or even money-positive (don't smoke, get a little exercise, eat fruits and vegetables, wear sunscreen)

But yet we as a society are so much more interested in giving our money to snake-oil salesmen for untested bunk.

It was very, very muddy at the Rage of Oz in Benton, Kansas. I could see much better than my glasses would indicate, though.

*MAMIL nomenclature unabashedly stolen from Code Switch:

Since I'm a MAMIL most days, at least for an hour or so, and since I know that even weekend warrior-style sporting activity is associated with a 34% reduction in the risk of dying, a 40% reduction in the risk of dying of a heart attack, and a 17% reduction in the risk of dying of cancer, I headed out to Benton, Kansas today for the final race in the Rage Against the Chainring series, the "Rage of Oz." This is the Land of Oz, after all, or the "Land of Ahs" if you prefer:

And, well, we've got us some rage:

*may or may not be from Kansas. But probably is.

So there we were, slippin' and slidin' through the Flint Hills south of Benton, Kansas, for 50+ miles:

It's not as flat as it looks. And for all you mathy-types, it was a two-lapper.

The end result was 4th place in the "B" class (sort of like scoring in double digits in the JayVee basketball game), but also a Saturday morning that I'm proud of and a statistically lower risk of dying today or tomorrow.

And some very muddy legs:

You can get a Belgian suntan even on cloudy days. In fact, more Belgian suntans are acquired on cloudy days than sunny days.