Having taken a bold stand against the onslaught of low-value data, I'm inspired to voice related opinions. If you've read much here at all, you already know that I believe that good health, like a good life, is achieved deliberately. Your time is precious and it's worth something. Your money is precious and shouldn't be mindlessly wasted on trivial crap. Moving through space under your own power prolongs your life, saves you money, and will help prolong humanity's life on planet Earth. And so on.

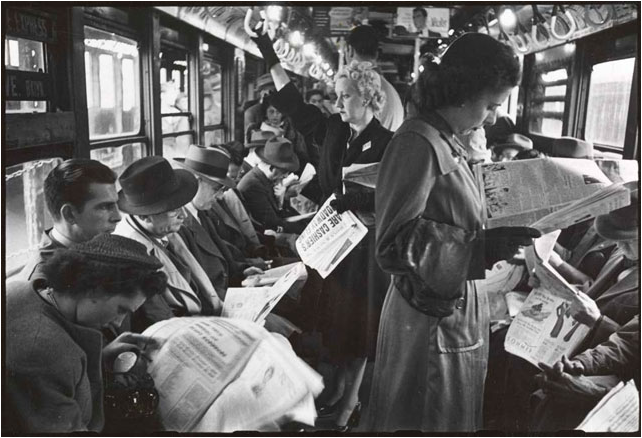

You may wonder why I don't just put these opinions in a Facebook page or Twitter feed. I'm glad you asked. Pictures like the one at the top of this page (taken by a young Stanley Kubrick, fyi) are plastered all over the internet with snarky memes like "All this technology sure is making us antisocial!"

But that take on a picture of people reading the newspaper fundamentally misses the point of the experience these people are having. To illustrate what I'm saying, it might be best for me to tell my own social media story:

Over the last few years, but not always simultaneously, I had accounts with Facebook, Snapchat, Twitter, Google Plus, Doximity, Pinterest, Instagram, LinkedIn, Sermo, and probably several other social media platforms that I can't remember now. I still have a LinkedIn page, but I tend to think of Linked in as social media that doesn't even try to tempt me. If you spend enough time on my LinkedIn page, you might see a moth fly by, or a tumbleweed ramble across the page. So I'll give it a pass. But the rest of those accounts are gone. Over the next few posts I'm going to try to tell you why:

1. Social media is expensive

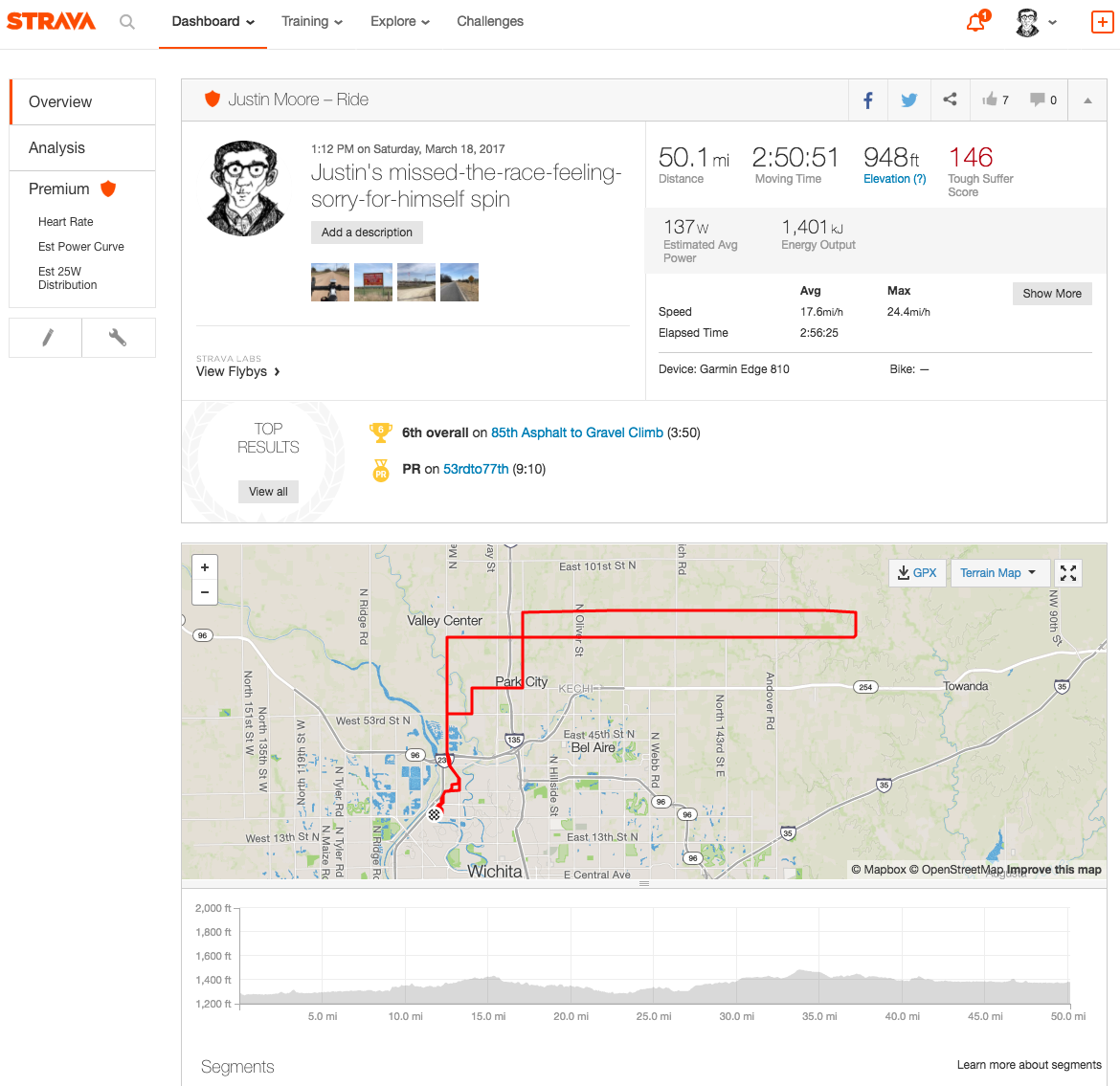

The value of your life isn't simply a matter of how many checks you write versus how many checks you cash. So the next time you download a "free" social media app, think of what it's costing you. The developers are betting on their ability to get you to pay in privacy and time, mostly for the sake of being able to stick cleverly disguised paid advertising in front of you. The average American spends three hours (!) a day on social media, 50 minutes on Facebook alone, more than the average two-way bike commute (which is a habit that actually makes you money, along with making you happier, healthier). So if it helps to put a monetary value on all that time (the equivalent of 6 years and three months of your life over the next fifty years), let's do a little thought experiment: at the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 (good Lord, I hope you're making more than that), that three hours a day equals $5,655 a year you're paying for the privilege of being on social media. And that only includes weekdays. If you include Saturday and Sunday, you're giving up $7,917 a year. And that astonishingly huge amount of money doesn't even account for what would happen if you worked a part-time job those three hours and put that money into some safe, reasonable investment vehicle and let it sit. It makes whatever the people in that train above paid for those newspapers seem pretty reasonable, right?

But it's not just the raw amount of time. In my social media heyday, I put an excessive amount of energy into tending to my online doppelgänger. I blush in shame now at the thought of what I must have missed out on by spending parties and nights out sweating for the next post, tweet, or 'gram. And for what? The little dopamine rush I got with every retweet was tiny in comparison to the feeling I get with good, old-fashioned excitement or awe. I wondered what all that energy could have done if it'd been redirected away from the construction of my online fictional persona and toward making my true self better. So I stopped. I stopped because of the opportunity cost of three hours a day, sure. But I also stopped because I'm not someone who's good with a one-liner; my mind needs time to work.

And that's what this little shout into the void is about. My pledge here is to take some time to think things through (turning up my own "bass," I guess) so that I know I've spent more time writing and thinking about a post than it will take you to read it. So even if none of you read this, the process will have somehow improved me.

There. Better already.