A year later, the Rio Olympic sites are ruin porn.

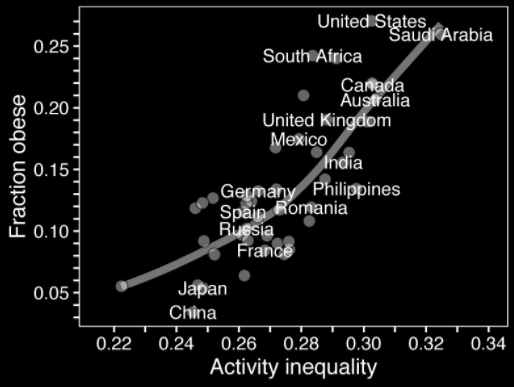

Is money the secret to making the Mediterranean diet work?

To be fair: I don't know a lot about this literature at all, but I suspect that the same claim could be made of many interventions, dietary and otherwise, were the data known. The more money you have, the healthier you are in general. (link via kottke.org)

Knowing our DNA risk doesn't make us change our behaviors.

I need to investigate this further. The thrust of this article--that knowing our risky mutations doesn't make us behave any differently--flies in the face of some data I've presented in the past.

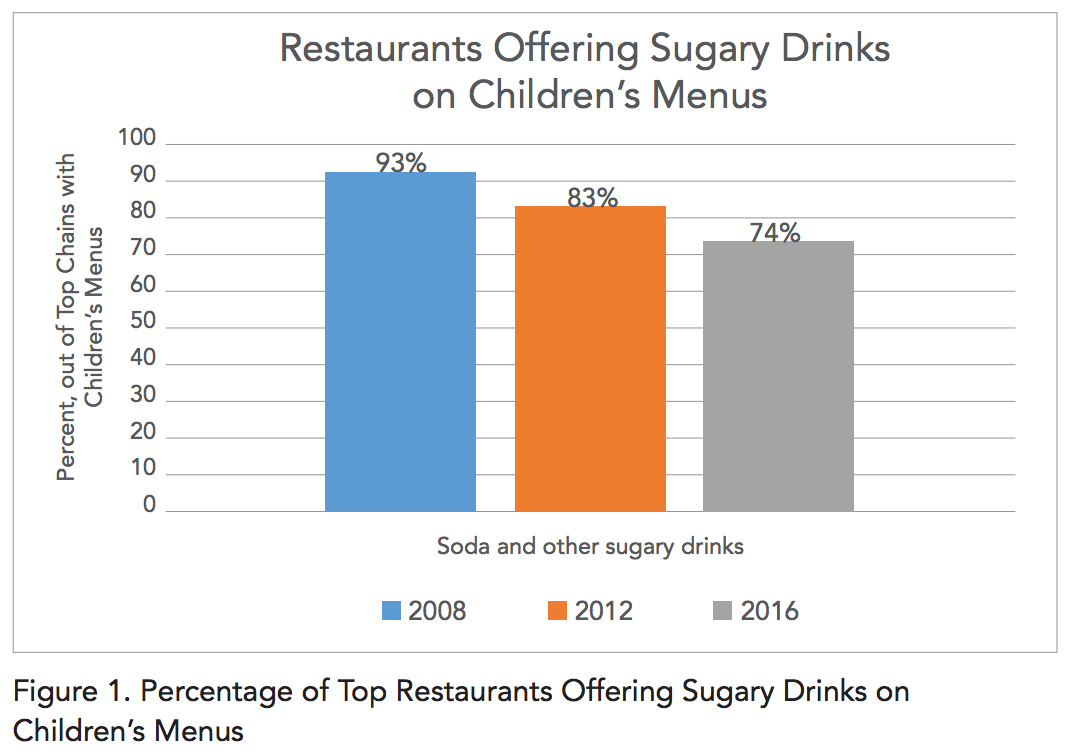

Have we all fallen for "clean eating?"

I remain convinced that eating food that looks like food, in the Michael Pollan sense, is generally what we should all be doing. Like most ventures that people look to capitalize on, though, it has been taken too far: see the "influencers" in this article that actually make themselves sick with adherence to an irrationally vegetable-based, uncooked diet. (link via longform.org)